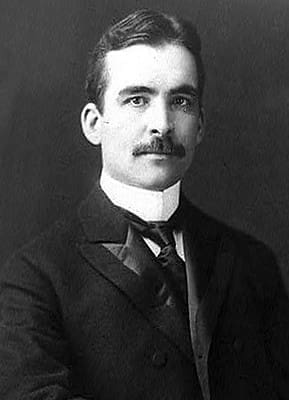

By Ron Wilson, director of the Huck Boyd National Institute for Rural Development at Kansas State University/Image: Charles Marlatt

Last week in this column, we learned about David Fairchild, an historic food explorer. Today, we’ll meet an historic food protector. Together, these men were two of the nation’s leading scientists at the time, and both of them came from rural Kansas. We’ll explain how their lives intertwined – and conflicted.

Charles Marlatt was an internationally renowned entomologist. He was born in 1863 in the rural community of Atchison, Kansas, population 10,885 people. Now, that’s rural.

Marlatt’s father was Washington Marlatt, principal of Bluemont College in Manhattan, Kansas. Washington Marlatt is said to have played an integral part in transitioning the college to become what is now Kansas State University. He is honored as the namesake of K-State’s Marlatt Hall. The Marlatt historic home and barn still stand on the K-State campus.

Young Charles Marlatt had a strong interest in insects. He heard that a famous British naturalist named Alfred Russel Wallace was coming to Kansas. He told this to a neighbor boy, his friend David Fairchild, who we learned about last week. Fairchild passed this information along to his father, who was president of Kansas State.

President Fairchild invited the British scientist to the Kansas State campus and to his home, where the scientist’s stories of his travels studying species in faraway lands inspired young David Fairchild to pursue such a career.

Charles Marlatt earned bachelors and masters degrees from K-State in entomology. In 1889, he joined the Department of Entomology at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It happened to be the same agency where his boyhood friend David Fairchild worked for the Office of Seed and Plant Introduction.

Marlatt had seen first-hand the crop devastation that could be caused by invasive insects.

In the 1880s, he was in California where he saw fields infested and destroyed by an insect pest that originated in China. Marlatt took an expedition to Asia in a desperate attempt to find a natural predator to control the invader. He found one: A red-and-black beetle so graceful and feminine that it was called the ladybug.

Marlatt’s ladybugs were the first in America, and they successfully controlled the damaging insects.

When Marlatt married, he took his wife on a trip to China – part honeymoon, part official business – to scout for more scientific information about insects. Tragically, Mrs. Marlatt suffered and died from internal parasites.

Marlatt served as best man at the wedding of David Fairchild. However, their career directions were on a collision course: Fairchild was the foreign crop discoverer, and Marlatt was the domestic crop defender. They became rivals.

While Fairchild was traveling the world identifying samples of new crops and plants to bring back to America, Marlatt was working to protect domestic crops from parasites, insects, or diseases from abroad.

When Fairchild brokered the gift of cherry trees to the U.S. from Japan, Marlatt insisted on being present for the inbound inspection of the trees. Sure enough, Marlatt found that the trees had multiple pest infestations. The Japanese were mortified and quickly sent clean replacements. Those trees now grace the Tidal Basin in downtown Washington DC.

Marlatt felt so strongly about the need to protect American crops that he led the effort to have Congress enact plant inspection laws. In 1912, Congress enacted the Plant Quarantine Act. The law did not prevent imports but required their inspection. Today, USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service continues to protect American crops and livestock from foreign infestations.

Charles Marlatt passed away in 1954 – the same year as…who else?…his boyhood friend, David Fairchild.

Among the buildings on the K-State campus today, there is a Fairchild Hall and a Marlatt Hall – each named for the fathers of these two men. Currently, Fairchild houses administrative offices and Marlatt is a residence hall for students.

It is coincidental but perhaps fitting and symbolic that these buildings have different purposes and are located at opposite sides of the campus. In their own different ways, both Fairchild and Marlatt contributed to the strength and productivity of American agriculture. One’s role was to diversify America’s food supply, and the other’s role was to protect it.