If you acted up in Gary Unruh’s mechanics or metalworking class, chances are you stood on a bucket. Five gallons, upside down, with a troublemaker perched atop it for the rest of class.

That was one of his better ideas, Unruh said, laughing about the tactic.

“Some would go around and bother other people so I would make them stand in one spot, then they’d get teased about it too,” he said.

Teaching up to six classes a day at CCCHS, Unruh was a staple from 1966 until 2003. Most of those years taught in the very shop he helped design. In total, he taught for 43.

Unruh, who had a master’s degree in industrial education, was recruited by former principal, Ed Butterfield. At the time, the school was looking to add programs for students who weren’t in ag, he said. Along with the superintendent of the time, Chuck Stewart Unruh helped to design the shop, along with the programs he would teach.

“The shop was built and it served its purpose for 37 years,” he said.

In his classes, Unruh said there were all abilities – from those who knew their way around a toolbox, to those who were beginners.

“There was a range of skill levels, but I always liked the exuberance of students,” he said.

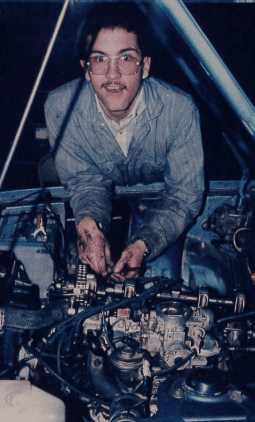

Unruh’s power mechanics class, April 21, 1992. Left to right: Jeremy Crimmins, Eric Gepner, Jeff Germann, Corey Pfizenmaier, & Bob Turner.

Teaching up to six classes per day – three mechanics, including a beginning and advanced, and three metal working – Unruh said students would enroll early, as classes would fill up. His most dedicated students would take four of his courses in total.

Teaching was also helped by a car that was donated by the Skinners’ former car dealership, a 1990 Cadillac with cosmetic damage.

“That was a wonderful teaching aid, it had the same controls for fuel and timing that other GMs had,” he said. The vehicle stayed in the shop until Unruh retired, then was sold by the district, he said.

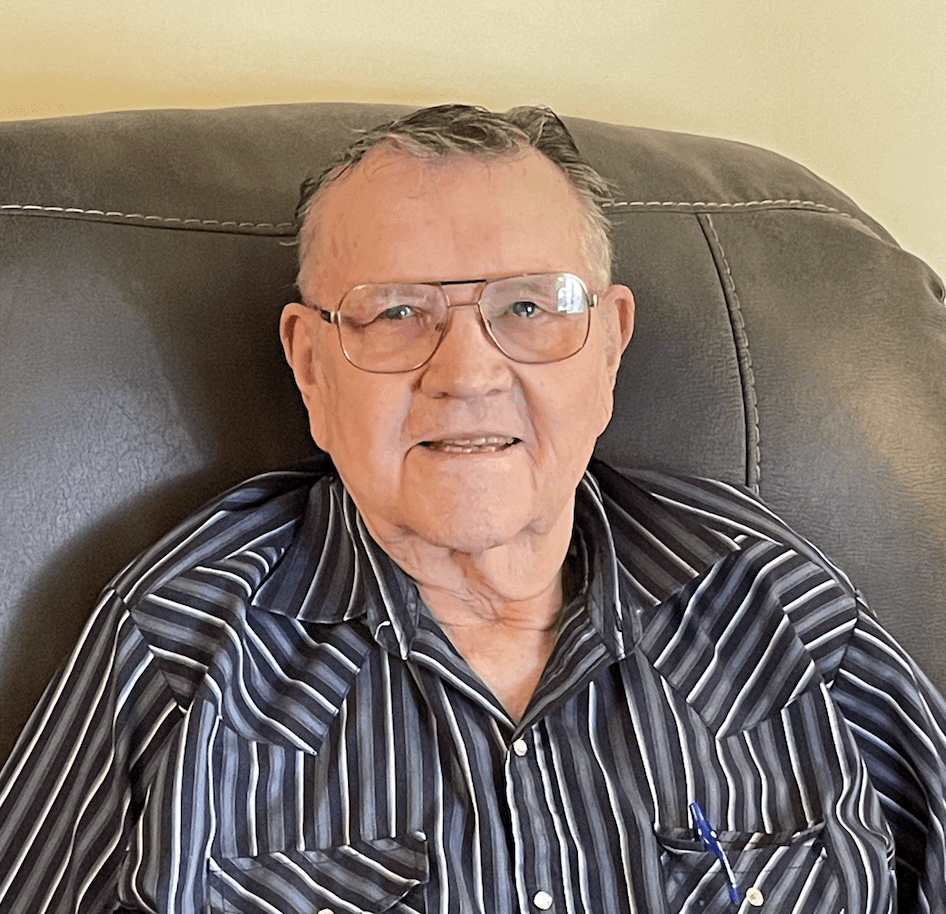

Now 85 years old, Unruh still tinkers in his shop – the idea to build it was his late wife, Nola’s, who wanted him to have space to fix. The pair met in college and were married 62 years. He also served as her caretaker after Nola was diagnosed with Parkinson’s.

“When you lose a mate it really takes a toll on you,” he said of his “despondency,” adding that he’s spent less time in the shop since losing his life mate. But hopes to continue in order to keep himself busy; he said he’s not done fixing things just yet.

In all, Unruh said it was his love for teaching all those years that fueled him to keep going. In total, he estimates 2,500 students who came through his shop.

“My number one goal was to inspire students to take some pride in their work and get some satisfaction,” he said. “They could develop some troubleshooting technique and learn how to evaluate what your problem is. If you don’t know, don’t be afraid to admit you don’t know and get some help.”

For his decades of teaching, Unruh was placed in CCCHS’ Hall of Fam in 2014, one of many teaching awards he received. In 1985 he was named Most Ambitious Teacher for his power mechanics class, and in 1972 he was named Outstanding Young Educator.

Fixing things was easier then, though.

“Of course it wasn’t that complicated in those days,” he said. Explaining that the addition of computers, sensors, and more has steepened the difficult of fixing.

One of Unruh’s proudest events has been keeping up with students. Those who became mechanics would call for advice or to check in, he said. Then, as vehicles got more detailed, the script changed and he was the one calling them for tips.

“What I enjoyed the first number of years was answering questions. Kids would come around or call, and now they know more than I do. It changed a lot. You still have to go by the basics, but it got to the point where I was the one calling them. They’re my teacher now.”

He also shared one of his proudest accomplishments was feedback he got from a former student – explaining that Unruh taught him there is more than one way to do something.

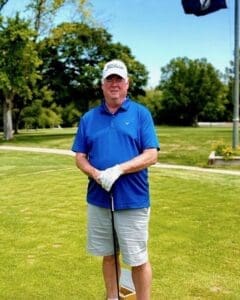

This picture features one of Unruh’s former students, Mayor Jimmy Thatcher in the mid 80s!

Thatcher went on to become an aluminum welder in the Navy. He was one of only two in his unit to earn the gig. Thatcher was asked if he grew up in his Dad’s shop, due to his superior welding skills, Unruh said. While the former answered he had learned in his high school shop class.

Patience Meets Pranks

Not surprisingly, working decades, teaching teenage boys came with its fair share of pranks. Adding that only a few students took it too far and – many later apologized, even if later in life – and most acted all in good fun. Even in disrespectful, Unruh said he put those events in the back of his memory, stating it’s a part of growing up.

Instead, he would redirect them, when students challenged him to see who could make a better weld, he’d play. Some of them could weld better, too, he said.

One student cut the wires to the diagnostic computer and the Cadillac car and Unruh turned it into a lesson on re-splicing wires. He made everyone help, with the perpetrator doing most of the work. They would often switch wires or parts when he wasn’t looking, waiting for him to figure out the change.

“Maybe I liked teaching more than some because I put up with it,” he said. “Most were just in good fun.” Adding that his trick for learning who had done a prank was never outright asking, but querying who should he talk with. “They wouldn’t say who did it, but they would say who knows something.”

One day after school, his truck – a ‘70 Ford, bright blue – one everyone knew was his – wouldn’t start. He found the distributor rotor in his desk.

“How thoughtful it was for them to put it there,” he joked in his signature inflection.

Then on Halloween in the early 80s, he parked in the shop to avoid getting his windows soaped. But when he went to retrieve it, the truck wouldn’t move. Unruh said the drive shaft was gone and – searching around the school – found it in the rafters of the locker room.

“Some of my good students came in early in the morning to see my reaction; they volunteered to put it back in,” he said of the perpetrators. “That was a good prank.”

But overall, he said even a little horsing around wasn’t always a bad thing.

“Even when they were ornery you didn’t encourage them to be more ornery because that could cause an accident,” he said. “But I’ve found if people didn’t have a little orneriness in them then they were lethargic.”