Hays, Kan. — With a family of five and a farming operation to run, Clay Scott’s home internet didn’t come close to cutting it.

Pulling up a weather page in a browser could take so long it produced an error message rather than a forecast. He tried installing a wireless security system, but it sucked up so much bandwidth that nothing else in the house would work. Once when his son needed to email a school project, the rest of the family had to log off just to give their connection enough capacity to send it.

“Today, we really expect it to be: Snap your fingers, here you go,” Scott said. “So it was definitely a challenge.”

Like many rural Americans, Scott’s home in southwest Kansas connected to the internet over an old copper wire. A better-than-nothing update on century-old telephone technology that struggles to handle Zoom calling, video streaming or a myriad of other internet uses that people in big cities largely take for granted.

Federal and state governments have poured billions into trying to bring more bandwidth to the remote corners of the country. But for many people in rural places, it hasn’t made any difference. An estimated 42 million Americans still don’t have high-speed internet, or what most people today simply think of as internet.

With fiber-optic cable installation costing tens of thousands of dollars per mile, it’s unlikely that big national providers will ever find a way to make money — or even avoid losses — by hooking up people like Scott in rural Kansas.

Ideatek / Ideatek: An Ideatek fixed wireless tower stands next to a road in Chase County just west of Elmdale. Towers like this send out a wireless signal that can connect any home within the line of sight and link farm equipment to the internet for precision agriculture applications.

But a growing number of small towns, farms and ranches are finally joining the Digital Age with help from small, local companies that have more of a stake in the rural areas they call home. They’ve found ways to stretch state and federal subsidies to strategically install high-capacity wires to homes, or construct over-the-air relays, to bring more robust speeds to remote outposts, town-by-town, farmstead-by-farmstead.

Now, with $42 billion in new federal broadband funding about to go to state governments, those local companies say how much money they get could decide how many more rural Americans get connected.

Return on investment

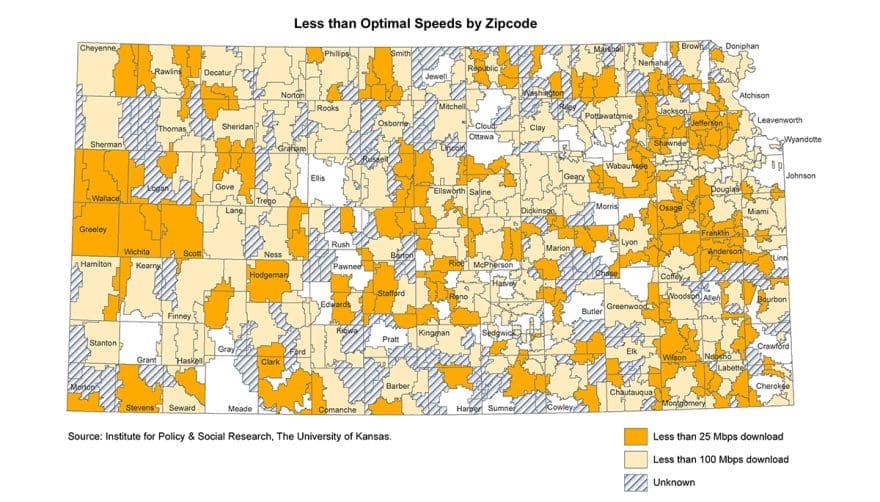

A recent survey study from the University of Kansas found that 95 Kansas ZIP codes — representing nearly 90,000 people — don’t have internet speeds that meet the federal definition of broadband.

And it’s not only a challenge in remote western Kansas communities. Rural parts of the state’s most populated counties — Johnson, Sedgwick and Shawnee — also fell below the broadband line.

KU economics professor Donna Ginther, who was the study’s principal investigator, said the reason is obvious: The economics of connecting such remote areas just don’t work out on paper.

“It’s really expensive to provide high-speed internet to a few people,” Ginther said. “That’s why you don’t have that infrastructure out there.”

Institute for Policy & Social Research, The University of Kansas: This map from a recent University of Kansas survey shows which internet speeds people use in each ZIP code. The study says the sections shaded orange don’t have access to speeds that meet the federal minimum standard for broadband.

But local providers like Ulysses-based telecom cooperative Pioneer are finding ways to make the numbers work one mile at a time.

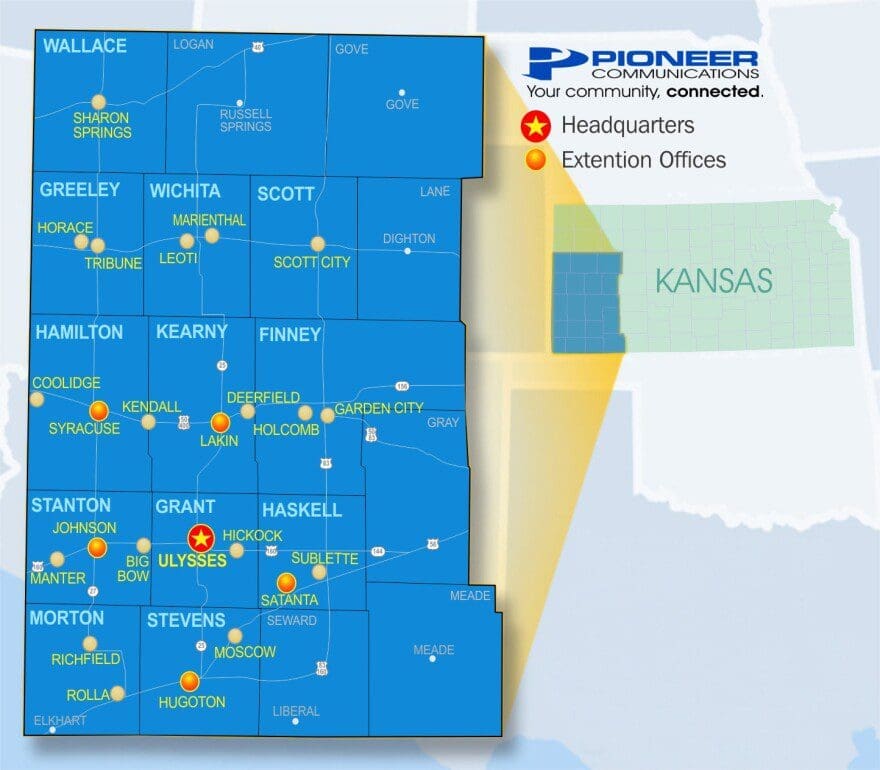

Pioneer CEO Catherine Moyer said the co-op’s goal is to connect everyone within its roughly 5,000-square-mile footprint in southwest Kansas. To do that, the co-op needs to get creative, stretching the financial feasibility limits with business plans that the AT&Ts of the world might scoff at.

But, she said, the fact that Pioneer isn’t AT&T is exactly what allows the co-op that flexibility.

“While we need to make money to continue to exist, we don’t answer to Wall Street,” Moyer said. “We don’t answer to shareholders. … We have member-owners.”

Christopher Ali, a University of Virginia professor and author of the book “Farm Fresh Broadband,” said this dynamic explains why local providers like Pioneer offer the strongest option for wiring rural America — as opposed to national companies like AT&T or Comcast. Their long-term business goals hinge on how to turn, say, $20,000 into a mile of fiber-optic cable in the countryside rather than a return to stockholders.

“If you think about it as an investment in the community, versus how much time you’re gonna need to recoup your return on investment,” Ali said, “that’s two very different ways of looking at that $20,000.”

Even though a local company like Pioneer and AT&T might both be telecom providers, Ali said, they actually have entirely different business models.

Ideatek / Ideatek: An Ideatek contractor installs fiber in Ford County in southwest Kansas.

For rural companies, seeing their region survive and thrive is the return on investment — and their best hope for staying in business.

“We interact with our customers on a daily basis. At church. At the grocery store. At the high school football game,” Moyer said. “So there’s an interest in seeing communities succeed.”

Pioneer started in 1950 when local farmers banded together to bring telephone service to the sparsely populated corner of Kansas. It now has around 100 employees and 10,000 broadband customers.

And roughly three out of every four customers are connected to fiber internet.

For those who aren’t, Moyer said, Pioneer plans to build fiber lines to reach them over the next several years. For example, the co-op is about to finish upgrading the town of Satanta from coaxial cable to fiber. That will give the community of around 1,000 people internet speeds up to 250 megabits per second.

“We don’t answer to Wall Street. We don’t answer to shareholders. … We have member-owners.”

Just over an hour’s drive from Satanta, another small southwest Kansas town — Bucklin, population 727 — got its own gigabit-speed broadband installed a few weeks ago by another local provider, Ideatek.

Bucklin is the latest in a line of several small towns along U.S. 54 in southwest Kansas that Ideatek has linked to fiber recently. Ideatek co-founder and Chief Innovation Officer Daniel Friesen said that at the start of the pandemic, the company took Meade County from 0% broadband connectivity to 95% broadband connectivity in the course of a few months.

Like Pioneer, Ideatek focuses on installing fiber to these rural places because it’s future-proof, with the speed and bandwidth to stay relevant for decades.

“While it may cost more,” Friesen said, “our position is that you need to do it right to really bridge the digital divide.”

Ideatek / Courtesy: Ideatek employee John Osborn installs fiber cable on a pole in the small southwest Kansas town of Minneola.

The last 10%

But installing that fiber in a far-flung place like western Kansas is hard.

Even if a rural company can get funding for a project, finding the team of 30 or 40 workers it takes to make it happen can be a challenge.

Moyer said Pioneer had to pull in a team from the Upper Midwest to handle its fiber installation in Satanta. For another fiber project in Garden City, it got a team from Oklahoma. And small providers like Pioneer have to compete with bigger projects from out of state just to land those teams.

It’s only going to get more competitive as a new wave of federal broadband money goes out.

“Everybody’s building right now,” Moyer said. “So it’s a good problem, but it’s also tough to find the people to do it.”

Recent supply chain problems have made equipment, like the fiber itself, difficult to get. Moyer said supplies that used to take 30 days to get might now take 250 days.

Then there’s the sheer geographic distance to cross with those fiber wires.

Pioneer: This map shows the towns served by the Pioneer telecom cooperative in southwest Kansas. The co-op now has roughly 10,000 customers, and three out of four have fiber high-speed internet.

Moyer said that out of Pioneer’s 5,000-square-mile footprint, only about 15 square miles are considered towns. And wiring the remaining 4,985 square miles, where customers are spread far and wide, becomes way more expensive per capita.

Imagine a graph that shows how broadband installation costs increase as the connection points grow farther apart. When it comes to connecting the last 10% of Kansans in the most remote areas — where a single home or farm might be several miles from any other connection point — that graph line accelerates upward exponentially.

“Those expenses are just astronomical,” Friesen said. “There’s just simply no way to do it without some level of subsidy.”

That’s where state or federal funding steps in to make construction possible.

But many rural areas don’t have enough workers and expertise to adequately compete for their share of government infrastructure grants.

A new map from Headwaters Economics that measures “rural capacity” — an area’s ability to handle everything it takes to apply for and implement state or federal money — shows that several western Kansas counties, including Morton, Gove and Cheyenne, rank among the most limited in the nation.

Headwaters’ research concluded that Kansas ranks as the seventh-worst state in the country for this measure of rural capacity. And the Midwest ranks as America’s most limited region — with three out of four Midwestern communities struggling.

The way the government has distributed broadband funds in recent years hasn’t done rural areas any favors either.

Ali, the University of Virginia professor, said the rural-urban digital divide persists partly because American broadband policy over the past decade has specifically favored big national companies like Verizon and CenturyLink over local providers — to the detriment of both those smaller companies and the communities they serve.

“We basically gave a ton of money to national incumbent providers,” Ali said, “and they largely failed.”

He said a clear example of this was in 2015 when the Federal Communications Commission’s Connect America Fund gave a group of 10 big telecommunications companies $1.5 billion a year for five years to deploy more rural broadband. By contrast, that same fund gave smaller local providers just $1.5 million a year for ten years — and that relatively meager amount had to be split up among 103 companies.

To make matters worse, Ali said the billions that the federal government handed to those large companies didn’t come with enough rules to make sure it accomplished its goals.

For one, the fund didn’t require providers to build fiber connections with FCC minimum broadband speeds — 25 megabits per second download. That meant companies could spend the money on outdated technology to give customers speeds that are already obsolete — 10 megabits per second. Some of the companies didn’t even install all the broadband they had been given money to do by the FCC deadline.

“We basically gave a ton of money to national incumbent providers, and they largely failed.”

And the FCC maps that determine where the forthcoming federal broadband funds are sent could end up funneling money to the wrong places because they don’t paint an accurate picture of which areas have the most need. Research from BroadbandNow shows that FCC numbers have likely undercounted the number of Americans without broadband by nearly 30 million people.

Ali said that combination of outdated technology, inaccurate information and poor accountability has put the country in a situation today where last year’s federal infrastructure bill included $65 billion to improve Americans’ internet access — but that still might not be enough to connect everyone.

“We’ve got pockets of complete unconnectedness and then other pockets of total under connectivity,” Ali said, “because we’ve been funding bad technologies for almost a decade.”

And broadband access isn’t the only issue keeping rural Americans offline — there’s also affordability. Rural customers within reach of broadband pay an average of 37% more than urban customers.

To truly bridge these access and affordability gaps, Ali said, the country needs to approach broadband’s expansion into rural areas much like it did with the Rural Electrification Act nearly a century ago.

“We didn’t say, ‘Well, you get enough electricity for one light bulb, and that’s enough,” Ali said. “That’s the same mindset we need for broadband.”

Ideatek / Ideatek: Ideatek employees John Osborn, right, and Jose Rios install fiber internet to the town of Minneola, population 738, last month. It’s one of several small towns that have been recently connected to Ideatek’s fiber line in southwest Kansas.

Out of the dark ages

Renewed interest in funding rural broadband projects at both the state and federal level could start to change that.

Ideatek and Pioneer applied for part of this year’s $5 million round of Broadband Acceleration Grant funding from the state, which will be awarded May 18. Starting May 16, Kansas will have the chance to apply for part of the $42 billion from federal infrastructure funding, which it could then dole out to local companies.

Meanwhile, many rural customers are stuck waiting.

“They’re going, ‘I needed that yesterday, and you’re telling me that … it could be a year or two years down the road,’” Moyer said. “That’s where I think the frustration lies.”

Even with great need and demonstrated success, Friesen said getting money from the state for broadband projects has been slow going.

Kansas got more than $1 billion in federal pandemic relief money last year that could go toward broadband projects in the state. But providers like Ideatek are still waiting for the state to distribute it, which Friesen said leaves Kansas lagging behind other states.

“If we as a state, or we as Americans, want to ensure that every person in Kansas or America has broadband service, there’s just simply no way to do it without some level of subsidy,” Friesen said. “Without it, there’s definitely a number of communities that would still likely be in the dark ages from a broadband perspective.”

Back at Clay Scott’s farm in Grant County, those dark ages are now over.

He’s planting corn this week with the help of four computer screens that access the internet for everything from GPS coordination to soil moisture monitoring to precise seed application. They all connect through a nearby Pioneer wireless tower.

“Once upon a time, we just hooked up the planter and filled it up with seed and went,” Scott said. “Today, it’s pretty technical.”

He said the amount of data he uses to manage his farm today is about triple what it was a decade ago. And having all that data at his fingertips has become critical to his operation’s efficiency, lowering his business costs and keeping seed and water from going to waste.

Pioneer recently installed fiber to Scott’s doorstep, too, more than doubling his internet speeds.

Even though his home is several miles outside of town in a remote part of Grant County — and likely cost a bundle to reach — his family now enjoys broadband that can rival just about any city in Kansas.

“They do it because it serves the community,” Scott said. “Sometimes it’s not financially the best decision, but it darn sure is in terms of meeting their goal of community service.”

David Condos covers western Kansas for High Plains Public Radio and the Kansas News Service. You can follow him on Twitter @davidcondos.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of High Plains Public Radio, Kansas Public Radio, KCUR and KMUW focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.