After years of frequent sightings, biologists in Kansas decided to investigate the cause of strange-skinned blue catfish. Listed as the rarest fish in some rivers and lakes, this sub-genre of bluecats have many nicknames: cowfish, ghost blues, and just plain lucky. They exist where the fish displays splotches of white skin (pibaldism) or no blue at all (leucism). And for years in Milford Lake, they’ve made a splash among anglers … to the point it was becoming a regular occurrence.

“It definitely seems like they’re more common now than even a few years ago,” said Ben Neely, biologist with the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks. “It just seems like we’ve been seeing them increase over time.”

Last summer the KDWP launched a full survey spanning 23 days, between May and July. They covered 11 ramps for six hours at a time, quizzing anglers on what they’d found.

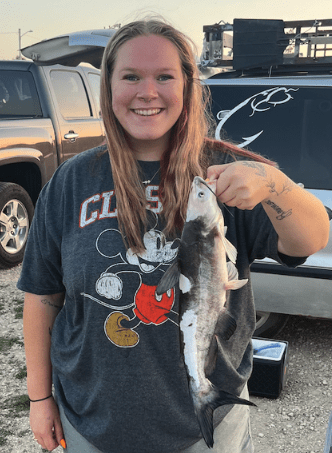

“Very few fish get a picture taken of them every time they’re caught,” Neely said. “These are picture fish.” He said some anglers said they were more likely to throw a pibald or leucistic fish back so others could enjoy it.

In addition, they performed their own electrofishing events to survey the number of altered bluecats found within the lake.

In total, 2,611 blue catfish were observed, of which 13.7% had piebaldism or leucism. (204 and 155, respectively.)

Neely said the survey was prompted from both biologist observation and comments from the general public.

“We found more than I expected; we didn’t really know what the number was going to be but I was surprised. I would have expected it to be a lot lower – we found almost 14% and that’s huge.”

The data also showed that an absence of color could hurt the fish’s camouflage options, potentially marking themselves to a predator. And normal bluecats grew to be bigger and heavier than their genetically altered counterparts.

“It’s kind of a gee-whiz thing that we are trying to figure out,” said Brett Miller, biologist with the KDWP at Milford. He, along with Neely, continue to collect data; Miller reported 12 leucistic bluecats the day he was interviewed.

“When we go out and do the surveys it’s like ‘There’s one, there’s another one.’ They’re pretty easy to spot when it’s a white fish popping up amongst the normal ones.”

The KDWP continues to study the fish, along with Emporia State University, Neely said.

“The long and short of it is we’re trying to determine what level is this genetic and how it can affect the population as a whole,” he said. “Is it genetically neutral or is a problem with inbreeding? We’re trying to mitigate and make sure the fishery is as robust as ever and people can continue to enjoy it.”

Neely said the different looks come from how the RNA is expressed in the skin.

“It’s triggered by different things, we’re looking at the RNA on different color species and trying to see how those genes are working together and how we can recreate this different phenomenon in fish.” Geneticists from the University will also help on the project, honing in on key data points for the fish’s DNA.

As for the cause, Neely said they can only look at the facts available to them. Piebaldism is a recessive gene, meaning it’s not visible. However, when a male and female who both possess the gene mate, their babies have the chance of displaying that trait or becoming a “visual piebald.” Two visual piebalds would also produce more visual piebalds, he said.

“The genes from both parents hit at some point and now they will just continue to become more and more common as they continue breeding.”

Those recessive traits likely date back to the early 1990s, Neely said, when the reservoir was stocked with blue catfish; the existing population of bluecats were almost completely wiped out after the lake was constructed. The KDWP likely introduced a bluecat population with recessive genes. Though Neely wasn’t with the department at the time, there is no record of visible piebaldism or leucism among the fish.

Neely said stocking fish is a waiting game of about two decades, with bluecats taking six-seven years to mature, and longer for multiple generations to reproduce. In addition, floods are great for fish population, he said, mentioning the 1993 event where Milford hit a record-high of 1189.90 feet. (In July of 2025, Milford Reservoir sits at 1144 feet.)

“Floods are generally really good for fish populations; they create a ton of habitats. They’re typically what we see as big reproduction events,” he said. “There’s more space, more food. By and large when we get those floods, it’s really beneficial for fish populations.”

Today, the population of bluecats is strong within Milford, and that includes the high percentage of those with unique marks.

“You can go out whenever now and find them, it’s not hard,” Miller said. With Neely reflecting that and commenting on how that differs from other bodies of water.

“Elsewhere it’s rare, very rare,” Neely said. “Milford is much, much, much higher than it is probably anywhere else in the world. The comments we always hear from the public is ‘It’s much more common in Milford than it is anywhere else.”