By JULES LOH

This story was published by the Los Angeles Times on October 30th, 1988

CLAY CENTER, Kan. —

Back during the Great Depression, Loyall Newell’s father thought his son frittered away entirely too much time hanging around the pool hall. It turns out it wasn’t a misspent youth after all.

“My dad would pay me $30 a week to help out in his garage,” Newell recalls. “I could make that in half a day on a snooker table.”

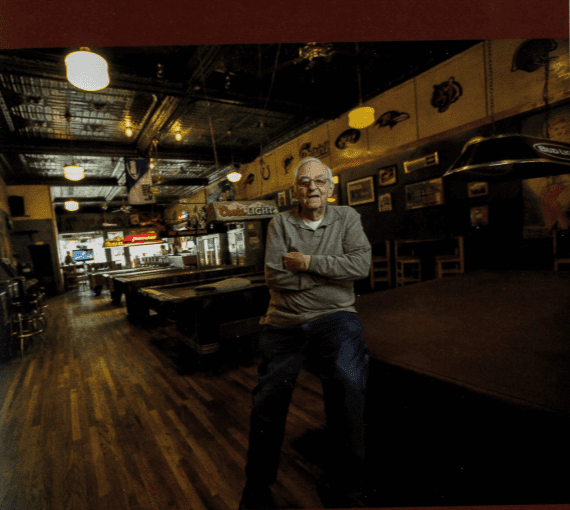

At 63, Newell still shoots a mean stick, as they say over at the Idle Hour, where Newell had idled away many an hour in his young manhood. He’ll still take on anybody in Kansas at three-cushion billiards, you name the bet.

Different Kind of Artistry

It is not his artistry with a cue stick, though, that has brought him the big payoff. It is artistry of another kind.

Today, Loyall Newell is one of America’s leading authorities on pool tables, and one of only a handful in the land able to restore to its original romantic luster one of those heavy old carved and inlaid beauties built more than a century ago.

“We’re not talking about just refinishing,” he says, “we’re talking about restoring. I replace missing parts with original parts because I have the parts. Not many others do. Then I refinish it.”

Right now he is busy restoring a table that has been in the Kansas governor’s mansion for generations and is getting ready to restore another that Mark Twain played on at his home in Elmira, N.Y. Newell’s handiwork decorates private rec rooms and fancy clubs in a dozen states.

Benefited From Misfortune

Ironically, Loyall Newell’s good fortune results from what many perceive as a great American misfortune, the demise of the family farm.

After World War II, when small farmers by the thousands began leaving the land for better paying factory jobs, rural towns across the plains withered and died. The local pool hall was often the first to board up its windows.

“This was happening when I got out of the Navy,” Newell recalls.

“I had a feeling somebody was going to want all those pool tables someday, so I started buying them up for practically nothing. Besides, I just like pool tables, those old ones. I think they’re beautiful. Historic, you might say.

“The first ones I bought were four old mahogany tables from a place over in Geary County. I also took all the cues and racks and equipment, and the back bar and front bar to boot. Paid $60 for the whole shebang. Some owners gone broke would be glad to take $25 a table just to have me cart them away.

He Was Right

“I did that all around Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, bought out 75 or 80 pool halls. It turned out I was right. I could get $200 or $300 apiece for them, depending on the condition, from people who wanted a fancy table for their homes. I put more than 350 tables in Kansas City alone, another 75 or 80 in Topeka.”

It was still only a sideline. Newell had bought the Idle Hour and run it along with holding a part-time job in the post office.

Then one day in the late ‘50s, an antiques dealer from the West Coast came through Clay Center and offered Newell $800 for four tables Newell had picked up for $200. Not bad at all. Quadrupled his money.

But Newell later learned that the dealer had refinished the tables and sold them in Los Angeles for $3,500 each.

“There I was with a warehouse full of tables and boxes of parts, boxes stacked on boxes. That’s when I decided to get in the restoring business. Not refinishing, restoring.”

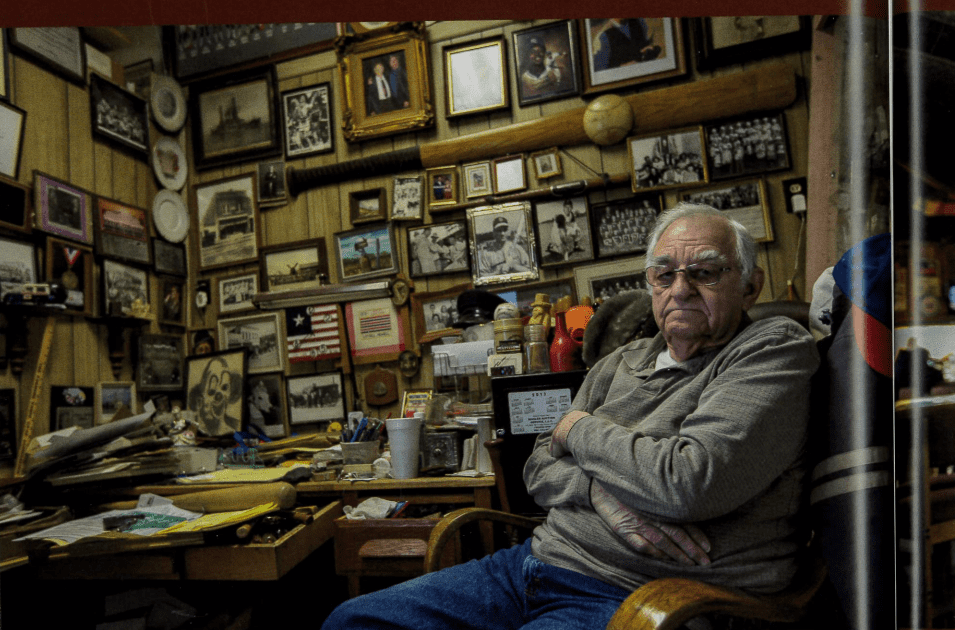

Smithsonian, of Sorts

The business grew to more than Newell could keep up with. He sold the Idle Hour, retired from the post office, and some years ago his son, Joe, quit his job and joined his father in what became Newell Billiard Supply Co. People in the pool table business also refer to it as the Smithsonian Institution of pool halls.

That is because, along with all those accumulated tables and parts, Newell also has assembled what he believes is the nation’s most complete collection of pool table records and catalogues. They begin with the first ones put out by Brunswick-Balke-Collender Co., America’s oldest and largest manufacturer.

“The company changed management half a dozen times and lost most of its records in floods and fires,” Newell says. “So now they come to us to answer their inquiries. We’re their official consultants.

“What happens usually is that somebody will inherit or discover an old beat-up table with a cracked slate and the Brunswick name on it.

Referrals Help

“They ask Brunswick whether it’s worth fixing. Brunswick refers them to us. We tell them to take pictures of the end and side panels and send us the pictures. We tell them what it is and when it was made and how much it will cost to restore it.”

Leafing through the catalogues, Newell pointed out that there have been scores of designs over the years, many of them with names like war cries: Nonpareil! Eclipse! Monarch! Exposition! The catalogues also include specially designed tables for individuals, such as John D. Rockefeller and a number of foreign nabobs.

An old Monarch table, catalogue price $475 in 1875, now in top condition can fetch as much as $35,000 to $50,000.

Often, the price of a restored table reflects not only Newell’s skill but the scarcity of antique parts.

“Here’s a bolt,” he said, reaching into a drawer. “It holds the slate to the frame. It has 14 threads per inch. Not 12, not 16. They’re what came in the original tables and nobody makes exactly the same ones nowadays. Use any other and you’ll break the slate.”

The Smells of Creation

Newell’s shop is a wonderful scene of organized disorder, redolent with odors of hide glue, raw wood and linseed oil, the smells of creation. Only two or three restoration projects are on the floor at any one time. About 85 more tables await rebirth in a warehouse, work to be done between special orders and sold to any bidder.

“You never know what sort of person the customer will be, Newell said. “We fixed up a table for a man in Eureka Springs, Ark., charged him $7,140. When I delivered it, he paid me in $20 bills.”

Newell, at his work, is a model of patience. He does the tedious jobs, leveling, sanding, rubbing, without complaint. In no hurry, he might take an occasional work break, for old time’s sake, and shoot a rack of nine ball at the Idle Hour, which happens to be right next door.

Thanks to his memories of youth and his loving care, the Idle Hour appears today just as it did in 1936 when it was built. No coin-operated pool tables here, all classics, and a classic bar worn silk smooth by elbows.

Still Standing

Clay Center, out in remote northeastern Kansas, with a population of about 5,000, is one farm town that hasn’t yet gone under and boarded up its pool hall. It would be like boarding up a shrine.

Newell picked up the skills of wood finishing just as he learned pool shooting, by experimenting, asking around, discovering some tricks of his own.

“When I was a boy shining shoes at the Idle Hour,” he said, “I used green pool table cloth for that final shine. It popped nice and did the job.

“Know what I use now to polish wood? My old shoeshine brushes. Yep, I still have them. I didn’t throw them away.

“Come to think of it,” he said, “I don’t believe I’ve ever thrown anything away.”