On K-State’s first Day of Giving, the Department of Agriculture’s sorghum campaign received more than $15,000. Those funds will purchase sorghum – a nutrient-heavy grain – by the ton. As much seed as $15,030 can get, said Kinzey Cott, fiscal analyst for the Global Collaboration for Sorghum and Millet at K-State.

“A safe guess is 18 tons – it’s about $700 a ton – that’s how they measure it globally – then there’s shipping and freight.” Millet is another seed-producing grass, but won’t be purchased this round. The sorghum will be used internationally to help poor farmers thrive, and to boost local economies.

This project focuses on Madagascar, where the tons of seed will travel via shipping container on the back of semis, then by silage truck.

“It’s not the most efficient, there’s wind and that will take some seed with it,” she said. “But that’s what they have.”

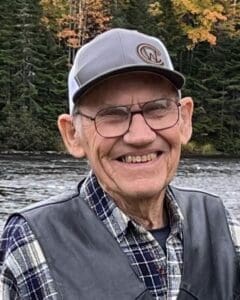

Cott, who has worked in international sorghum relations for five years, holds a master’s degree in Agricultural Economics. She said she was introduced to the career by a family friend.

“It was ag-based, but on an international scale and using grants,” she said. “It’s good to have international connections and farmers should be leaning more into grants, so I thought it would be a really good path for me to go into.”

In years since, she’s created personal relationships while helping coach farmers. With the goal being to create jobs and pump dollars into other economies, the program works with farmers not only in Madagascar, but Niger, Haiti, Ethiopia, and Senegal.

Cott’s department first sells the grain farmers, who grow the crop, then help them broker deals to sell it for livestock feed or flour.

The program promotes as much in-country growth as possible, which is done for two reasons. 1) the US has very strict rules about importing/exporting agriculture-based commodities.

“Keeping it in one country keeps you safer from a bio standpoint. You’re looking at risk of disease, contagions, pests and bacteria,” she said. Though other countries aren’t as strict, it means fewer logistics to move seed. “This is a challenge that we try to avoid.”

2) by getting the seed to international farmers, it gives them the opportunity for growth – with their plants and business.

“We don’t just give, the whole premise isn’t to just give things because that hurts economies,” she said. “We create an opportunity for a person to have a job or create another economic avenue for them to grow their own community.”

“I think a lot of people think we’re just giving federal aid. But we aren’t giving away money, we’re teaching people how to develop their own economies. We’re teaching them how to farm so they can be sustainable on their own.”

Part of the gig means determining which strains do best in various weather conditions, and following yields. For instance, because Madagascar is such a long country, Cott said they require two types of sorghum seed: one that does better in the tropical conditions of the north, or the dry season of the south.

“They’re growing different varieties to thrive in different conditions,” she said. Adding that varieties these countries are growing far differ from developed American versions.

“They don’t have the nutrients to support themselves structurally, so they need a thicker stock to grow taller,” she said. Describing Madagascarian sorghum as six feet tall with wide stocks. In comparison, Kansas sorghum is about four feet with a higher yield. “Theirs looks more like a corn stalk.”

Previously, the project was funded by USAID, or the US Agency for International Development, she said. Cott moved jobs after K-State’s Global Collaboration on Sorghum and Millet, lost funding in March of 2025. Because she works in finance, Cott said she was able to switch departments; now only a small portion of her job is managing the sorghum funding.

It’s one of the only programs from her previous gig that survived. At least 40 people lost their jobs domestically; internationally that number sits around 400, Cott said.

It’s her job to manage the funding, also known as a grant specialist. Before its main funding was revoked, that was a total of $70-$100 million programmatically. Now they’re down to about $300,000.

She estimated that about 20% of her job continues with sorghum.

Today, 70% of the world’s sorghum is used for animal feed, likely due to its bitter taste, Cott said. However, with the right baking mix, it’s edible, particularly a type of Ethiopian flatbread called injera.

“They’re wanting to push it more because it’s cheaper to make flour,” she said. And without electricity, production comes with no easy feat.

To further complicate the process, Africa has a large population of poverty, Cott said.

“The difference between the haves and have-nots is really big, there’s no middle class.” She added that the upper class is just half of a percent. For instance, one of the grain customers is the sole franchisee for KFC in all of Madagascar.

This nuance can be difficult when traveling, of course – Cott or other members of the team have often met with their farmers in person – though she’s no longer sure trips are in the budget.

“The team thinks I’m going,” she said. “But I do the books, mathematically, I’m not going. We have some grant proposals out, so there are chances for money to come in but getting a grant takes a long time.”

Previously Cott has traveled to Niger, France, and Cambodia, where she was fed goat’s head stew – she learned this after the fact when her cooks proudly showed her the skull.

Another part of the job is working with cultural nuances. For instance, an average daily wage for a Madagascar farmer is $2. Meanwhile, the U.S. is federally required to pay a daily consultant rate of $300.

“You can’t pay that without causing a bunch of uproar in their community, and it can be disrespectful of their culture,” she said. “It could be insulting them if you try to offer more. Or it would be giving this person a bunch of power.”

Cott has to get prior approval to pay the country’s going day-rate for their security, translators, etc., to avoid a faux pas.

“They’re good business people and very nice, but the way business is handled is different,” she said of the upper .05%. “There’s just a lot of games to play.”