Electric lights have been in Clay Center for 138 years, entering the area as a novelty when forefather, Alonzo Dexter, built an electric light plant in 1886. Within two years, downtown kerosene lamps had been replaced with bulbs, even while very few residents had electricity in their homes.

As a privately-owned power company, Dexter agreed to a contract with the town, containing a provision that light should be charged as cheaply as it was to any city in the United States. However, once he sold, the new owner, Williamson, Wickstrum, & Company wanted to amend the contract once it expired. At the time it was 12 cents per kilowatt, and they wanted to raise the rate to 20 cents.

However, because the power was generated by dam, the city argued that they were making money at just 5 cents per kilowatt. City Council voted not to renew with the company, who was doing business as Clay Center Light & Power Company. In 1905, the town was presented with two options: purchasing bonds to the tune of $20,000 or establishing and managing a board to operate and manage a power plant.

In 1906, with three years left on their contract, both options were voted into approval, followed by an additional approval of another $25,000 in bonds, for $45,000 in total. (Nearly $1.6 million today.)

However, Williamson pursued a court injunction to prevent the sale of bonds. The injunction was not issued. Instead, City Council notified Williamson, Wickstrum, & Co. to discontinue service, and take down its poles and supplies from all streets, alleys, and public grounds. The company’s owners refused, and again sought out an injunction and pursued the case for years into the future.

In November of 1910, a group of citizens gathered in early morning hours to cut down light poles and cut wires. It was stated in the Daily Republican that this was done under direction of the City Clerk and other authorities. A total of 13 poles were cut before they were caught by Williamson himself. The Times reported that he drew a revolver and threatened to shoot men doing the cutting.

A month later, the case made it to the U.S. Supreme Court. Though it was not decided until 1916, ultimately the Public Utilities Commission won.

“Municipal ownership won an important victory in a decision of the Supreme Court. The court holds that the 21-year franchise of the company has expired and that they city is not compelled either to purchase the plant or renew the [contract].”

Bringing Water to Clay Center

By the time CCPUC had its electricity infrastructure put into place, a water plant had been running for some time. Starting in 1883, it began when 65 citizens petitioned the city and put in private capital.

The City was hesitant with water as a business model, but leaned on additional safety features, like the ability to put out fires and allowed a private service to set up shop via Holly Water Works Company. Up to that point, three cisterns within the business district were the only way to extinguish downtown fires. The earliest fire engine was manned by 32 men, half on each side, and was said to be effective, so long as it was near a cistern. The men manually pumped water through a hose.

The first water main was underway by 1885, including five fire hydrants. However, just a year later the city found the water company in breach of contract, refusing to pay for the hydrant rentals. The City was subsequently sued. This case, too went to the Supreme Court where it drug on for years and was settled out of court. However, in 1888, the city voted to sell $35,000 in bonds to create a municipal waterworks system and the first Clay Center Water Plant was born.

The Great White Way

By 1914, the town was home to 22 miles of lights within the city streets. It was a bragging point of the community, to the point it earned the nickname of The Great White Way.

The lighting began with a baseball game between teams representing Court and Lincoln Streets, wherein the winner earned better lights for their street. The game brought in money from attendees, and those funds were used for the lights. The first game brought around $20, landing enough to put in four bracket lights on Court, the winner of the game. The businessmen of Lincoln didn’t want to be outdone and began collecting funds for their own lights.

In total, 250 lights fed by 7,170 feet of underground cable. In addition, 50- clusters of five incandescent lamps lit streets around the Courthouse Square and area business streets; 116 lights were also added at intersections.

A “New White Way” was upgraded in 1930 and another 80 lights added in the following year. The 1950s again saw new lights, including those that were triggered with darkness.

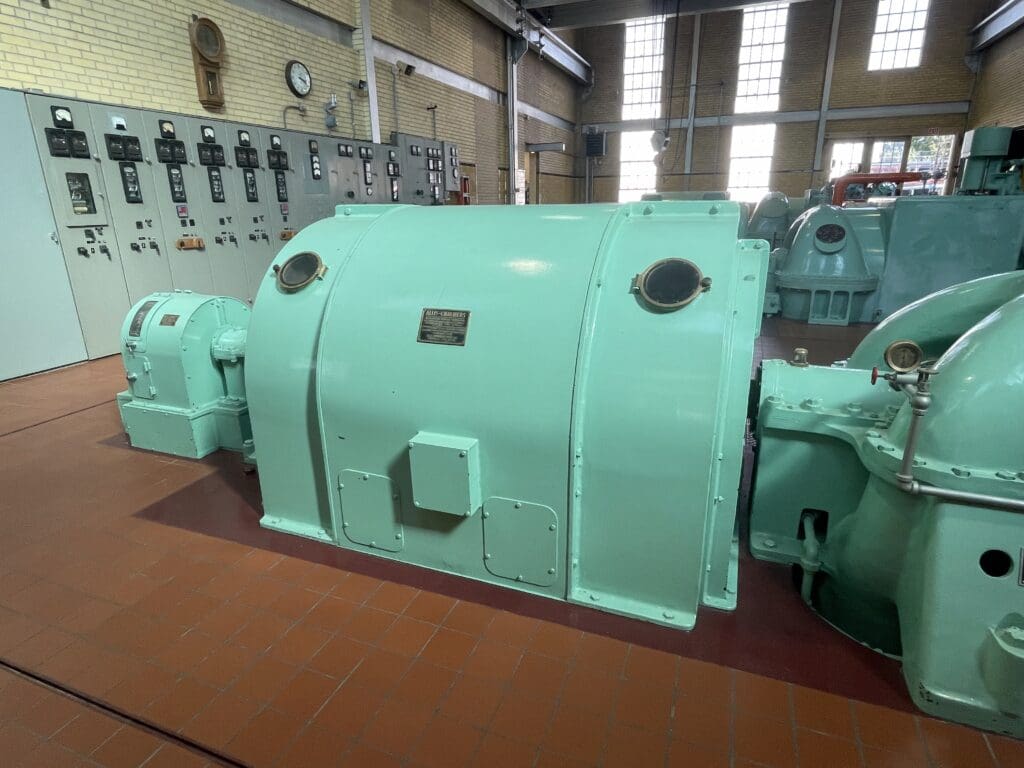

Today, the CCPUC hosts six dual-fuel generators that are capable of putting out 23,000 kw worth of power.

The oldest generators run on steam and the newest can run on either diesel or natural gas, allowing PUC to choose the cheapest source of fuel each day.

The machines are so large, they have their own concrete foundations, separate from the building’s floor. This keeps the vibrations and movement of the running machines from affecting the integrity of the facility itself.

Top: Scott Glaves, CCPUC Superintendent and Val Kondratieff, Power Superintendent. Middle: a generator and wall gauges in the Power Plant.