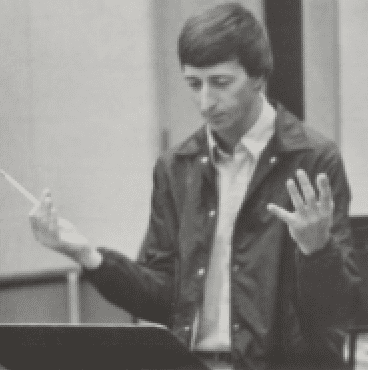

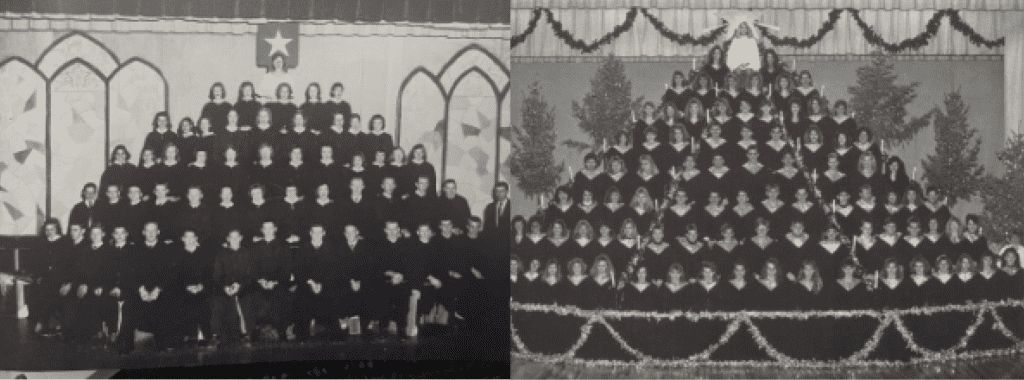

On December 14th, the CCCHS Singing Christmas Tree will celebrate its Platinum appearance with 70 years. First hitting the scene in December of 1956 in the former Clay County High School, newcomer vocal teacher, Jim Martyn, spearheaded the event. The inaugural event was called a “Christmas Vespers,” which included a 30-minute preclude of organ music, followed by 17 holiday numbers that were performed by a 45-member chorus and 15-member orchestra.

Students sat atop a tree made of cinder blocks and plywood seats to form a “tree.” The singing tree tradition had originated in 1933 at Belhaven University in Mississippi, then made an indoor appearance at a high school in Denver. Martyn then brought the tradition to Clay Center, which he intended to keep annually from the beginning, according to a 1956 interview.

The following year the event was called the Yule Vespers but followed a similar format. Lacking a vocal room, students practiced in the auditorium year-round. Before the second showing, Martyn had talked to the industrial arts teacher, Leonard Selig, about building a more permanent tree. With students, a short, stocky tree frame was built, while art students created a backdrop for the event.

That same frame was used until the current CCCHS was built, said retired vocal instructor Ken Lang.

“They put it up on the stage, which was much bigger than the one before, and it looked really small,” he said. “Leonard built a new tree that was nine rows high.” This one was taller and curved, more like an actual tree. It remained after Martyn retired in 1979; the auditorium was eventually named for him after he died in 1991.

As Martyn’s former student and predecessor, Lang sat upon both tree frames, sitting at the top AKA the “star” his senior year in 1965.

Just over a decade later, from 1979 to 2004, he was the one putting it together. An intricate act, Lang said there were three colors that indicated where pieces went: red, yellow, and green for left, right, and middle. The first year, Martyn showed him how it went together, as did Lang for his predecessor, and down the line.

“My goal in coming there, being a former student, I kind of knew the high standard that was set and the precedent to keep that alive and not let it sink. I kept the tree as a tradition and thankfully it’s still going.” I think we maintained a pretty good program.”

Lang also had to replace pieces of the tree frame through his tenure, including a time where a water leak caused warping.

“It’s an interesting tree when it’s bare and ugly,” he said. “You start at the top and work from there. You have to adjust and push the parts to get it all just perfect.”

The design was so unique that he was contacted by different schools, with whom he shared the original blueprints so they could create a tree of the own.

“One of the interesting things about the tree is it makes it difficult to sing,” he said. “All choral risers have a concave shape and you sing toward the center, but the tree you’re going the other direction so you’re singing away from each other.”

He said this was more difficult for kids on the outsides, who couldn’t hear across the tree.

Lang was also contacted by the Wall Street Journal, who wanted to cover the tradition around its 40-year mark. Ultimately, he and then-superintendent, Charlie Mansfield decided to keep the tradition local.

“We decided it was not a good thing to advertise what we do here in small-town, Kansas and we turned down the offer.”

At some point, it became tradition for students to sign the seat where a student sat, especially the star. Though Lang said it wasn’t a tradition he encouraged.

“They always kind of did it secretly and come in when nobody was around,” he said. “I tried to discourage it because with all the names it made it hard to put together. There’s writing that says, ‘This piece goes here’ and the names made it harder to read.”

Another practice the kids enjoyed was walking in while singing, though he only let them do it every few years.

“They had real candles and came in the back doors; the kids loved doing that but it was always kind of scary,” he said. “You had to trust them to do the right thing and get their spacing right, to not get too close and light the kids in front of them hair on fire. But it was very effective for a show.”

As the tradition got more popular, more and more kids joined choir, Lang said. There were a few years where he couldn’t fit everyone on the tree, which tops out at 105 students. He worked around this by splitting the freshmen girls into two groups, each of whom got to do a performance.

“It was pretty packed, and the kids were uncomfortable,” he said. “But that’s how we did it so everybody got to be on the tree.”

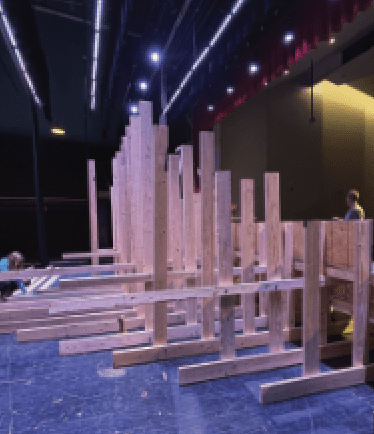

In 2017 the tree was replaced as the current vocal teacher, Kara Bergsten, said it had become unsafe. However, it still consists of large pieces of lumber and plywood. The week before Thanksgiving, her students bring up pieces through trap doors in the stage floor, then her husband, Jason, puts them together.

They also made the tree sit flush rather than curved, allowing kids to be able to hear one another. Bergsten said she asked for more safety with the tree, like railings and closed-in footing.

During the break, she will also come in to decorate and work on light configurations, which she said is easier to do without students in tow.

“There’s usually three or four light changes per song so it’s a lot of decisions and a lot of details,” she said. “We don’t have time to take away from class because we need that time to sing and practice.”

Bergsten, who sang on the tree throughout high school, took over as vocal teacher in 2015. Prior to her tenure, the program was ran by Zach Malcolm, another CCCHS vocal program alum.

“Zac and Kara were both students of mine,” Lang said. “And I was a student of Jim’s, which is pretty cool. 70 years is quite a long time and that’s only four directors; that’s quite remarkable for any vocal program. Then you can go back 100 years and it’s five total, that’s pretty phenomenal.”