Cawker City, Kan. — One day in 1973, The Wall Street Journal published a review of Kansas tourist attractions.

It was not kind.

“Kansas is trying to promote tourism,” the Journal noted, “but it really doesn’t have a heck of a lot to promote.”

The column singled out the godfathers of Kansas roadside tourism — the World’s Largest Ball of Twine in Cawker City, the World’s Largest Hand-Dug Well in Greensburg and the folk art town of Lucas — for particular ridicule, with pause breaks in the spots where the Journal expected its audience to chuckle at Kansas’ expense.

Local newspapers from Salina to Lawrence to Atchison responded swiftly and defensively, standing up for the state’s quirky attractions and the simpler-times spirit they represent.

“If modern Kansas only had some outdoor privies,” the Atchison Daily Globe quipped, “we would recommend a use for this Wall Street Journal.”

As it happens, the town of Elk Falls in southeast Kansas bills itself as the state’s outhouse capital and celebrates its collection of privies with an annual festival.

No matter how kitschy, these offbeat attractions can offer a boost to rural economies. Dozens of Kansas towns take advantage of their locations to tempt travelers to spend a few dollars while driving through “flyover country,” often on their way to somewhere more glamorous.

Just as importantly, the sites give communities something to rally around and a feeling that their hometown — no matter how overlooked — deserves a nod from the outside world.

“We hear that, ‘Oh, it’s just a hole in the ground,’” said Stacy Barnes with a laugh. She’s the city administrator for the town with the World’s Largest Hand-Dug Well. “Well, it’s true. But … it is ours.”

David Condos / Kansas News Service: Kansas’ larger-than-life attractions, like the Big Well in Greensburg, bring tourist dollars and community pride to the small towns they call home.

For rural areas that have seen a steady exodus of residents since their populations peaked more than a century ago, finding some way to bring in more revenue is a matter of survival. And for better or worse, Kansas isn’t blessed with the mountains or beaches that seem to effortlessly lure crowds of tourists to other places.

So if small towns around here want to stand out, they’ve had to come up with their own larger-than-life wonders to put themselves on the map.

Like a cowboy boot spur big enough to drive a semi-truck through (Abilene). An easel taller than an eight-story building (Goodland). A souvenir travel plate made from a 14-foot satellite dish (Lucas).

Or a ball of farmer’s twine the size of a shuttle bus.

“You do what you can with what you have,” ball caretaker Linda Clover said. “And we have a ball of twine.”

Going big

Despite decades of doubters and the Wall Street Journal’s best efforts, the quirky attractions dotting Kansas roadsides may still have the last laugh.

A sign next to the Ball of Twine today credits that Journal article with single-handedly elevating the site’s fame nationwide, setting off waves of out-of-state visitors that now stream through this tiny north-central Kansas town by the thousands each year.

David Condos / Kansas News Service: The World’s Largest Ball of Twine keeps growing as visitors to Cawker City wind their own pieces of string. It now weighs more than five Ford F-150 trucks.

Along the side of the highway that leads into Cawker City’s three-block downtown, the giant ball is impossible to miss. From its hilltop shrine next to an auto repair shop, it glows in the afternoon sun like an oatmeal-colored lighthouse beam beckoning travelers to drop anchor.

A retired school librarian who grew up in the next town, Clover took on the mantle of caring for Cawker City’s pride and joy more than two decades ago. She now lives close enough to the ball that, when she sees people stop by, she usually pops over with one of her twine spools and shows the visitors how to tie on their own piece.

“I call myself the crazy twine lady,” Clover said. “I’m the belle of the ball.”

This ball got rolling back in 1953 when a local farmer, Frank Stoeber, became sick of tripping over extra bits of twine leftover from tying up his hay bales. So he began winding those scraps into a ball. Soon, that ball grew big enough to fill a barn door.

David Condos / Kansas News Service: A sign behind the ball of twine displays old photos of farmer Frank Stoeber, who started the ball in 1953.

A few years later, Cawker City invited Stoeber to haul the ball into town to show it off in a parade celebrating Kansas’ centennial. And thus, one of the most famous tourist attractions in Kansas was born.

While the population of Cawker City has shrunk by more than one-third since that ridicule from The Wall Street Journal, the Ball of Twine’s size has ballooned along with its fame.

It now weighs north of 27,000 pounds, more than five Ford F-150 pickup trucks. And if you unraveled its 8.5 million feet of coiled twine, it would stretch from Cawker City, past New York’s Wall Street and all the way to the eastern tip of Long Island.

David Condos / Kansas News Service: Linda Clover lists off dozens of far-flung hometowns that visitors have written in the ball of twine’s guestbook. During the summer, she said, the ball welcomes roughly 200 travelers each day.

A glance through the ball’s guestbook (yes, the Ball of Twine has its own guestbook) shows dozens of visitors from as far away as Oregon, Florida and Italy. In just a few days.

During the peak summer season, Clover said, it brings in around 200 travelers a day — in a town of only 457 residents.

“I have had people so excited … they could hardly wait for the car to stop so they could come and see it,” Clover said. “And they keep coming.”

David Condos / Kansas News Service: Tourists use this spiral staircase to descend into the 109-foot-deep well in Greensburg.

It’s a similar story at the World’s Largest Hand-Dug Well, which last year drew 10,455 visitors from all 50 states and 14 countries to Greensburg, a town of just 740 people east of Dodge City. Out-of-state visitors far outnumber Kansans.

Jack Benigno, from California’s San Joaquin Valley, already visited the well six years ago. But when he planned this road trip through southwest Kansas — which included another quirky stop at Liberal’s Land of Oz — he purposefully made time to descend into Greensburg’s hole in the ground once more.

“I love it,” Benigno said. “And I love Kansas.”

The well also has the distinction of being the oldest world’s largest thing in Kansas.

It dates back to the 1880s when Greensburg’s founders sought a way to attract more people to their new town. So they carved out the type of sensational water source that’d be something to write home about.

David Condos / Kansas News Service: A collection of tchotchkes that tourists have bought from the Big Well museum over the decades, from buttons and plates to a tiny plastic toilet.

And as the name suggests, the massive well — 109 feet deep by 32 feet wide — was hand-dug. That meant teams of men shoveling out and carting up countless loads of dirt until they reached the Ogallala aquifer.

Visitors who come to the Big Well today follow in those footsteps, down a 120-step staircase that spirals its way toward the water table.

Barnes, who directed the well museum for 10 years before becoming Greensburg’s city administrator, has walked up and down these steps countless times.

“It’s just mind-blowing,” Barnes said, gazing up from the final step near the bottom of the well, “how they would have done it with nothing but hand tools and oxen.”

David Condos / Kansas News Service: Greensburg city administrator Stacy Barnes stands on the staircase overlooking the Big Well.

The well didn’t last too long as a water source for Greensburg’s residents. But in 1939, it got a second chance at life as a tourist attraction.

By 1956, the well had welcomed 1 million visitors.

In 2021, the museum’s admission fees and gift shop sales brought in more than $215,000 to this tiny community. And that doesn’t count the money tourists inevitably spent at nearby restaurants, hotels and gas stations before or after their stop at the well.

“It still keeps our community viable, just in a different way,” Barnes said. “Not for water, but for tourism.”

Kansas Tourism spokesperson Colby Sharples-Terry said these types of oddball attractions can translate into real economic benefits for small towns.

And she’s glad to see so many rural Kansas communities get serious about finding unique ways to stand out, even if those ways might seem unorthodox.

“They know that without change,” Sharples-Terry said, “the town’s gonna die.”

According to the state’s most recent data, tourism’s per capita economic impact in Kiowa County — home to the Big Well — is $1,651 a year. That’s more than three times the $544 per capita tourism impact in Edwards County next door. And that far surpasses other nearby counties in rural southwest Kansas like Comanche ($913) and Clark ($337).

It’s the same story for Cawker City. Tourism’s annual per capita economic impact in Mitchell County — home to the Ball of Twine — is $1,425. That’s way more than neighboring counties Jewell ($655), Lincoln ($520) and Ottawa ($422).

And even though the tourism dollars Cawker City and Greensburg generate may pale in comparison to bigger cities, Sharples-Terry said that revenue adds up here in ways that it wouldn’t elsewhere.

“If you go to Los Angeles, they won’t know that you’re there,” Sharples-Terry said. “But if you go to Lucas and visit these sites and eat lunch, that is directly impacting that community so much more.”

David Condos / Kansas News Service: Erika Nelson’s map of the world’s largest things in Kansas contains her miniature versions of the giant ball of twine, travel plate, hairball and more.

Small town superlatives

So what is it about these world’s largest attractions that has kept them relevant and profitable for so many years?

And why is Kansas — and the middle of the country, more broadly — such a hot spot for them?

That’s something Erika Nelson has pondered quite a bit during her time as a rural artist and world’s-largest-things aficionado.

“Kansans will try the craziest ideas in a very serious way,” Nelson said. “The naysayers get shut down pretty quickly.”

She would know.

Nelson’s not only a fan of the world’s largest stuff. She also created one of the quirkiest giants in Kansas: the World’s Largest Souvenir Travel Plate that greets travelers from the side of the highway as they drive into Lucas (population 394).

David Condos / Kansas News Service: Artist Erika Nelson stands in front of her own colossal creation: The World’s Largest Souvenir Travel Plate in Lucas. Nelson has been fascinated by the world’s largest things since she grew up in the shadow of the world’s largest 8-ball water tower (as seen on her shirt).

With an old phone company satellite dish as her canvas, Nelson painted it in the style of the gift shop tchotchkes tourists have taken home to their curio cabinets for decades.

True to form, she decorated it with a collage of illustrations that tell the story of Lucas — from the town’s over-the-top public restroom in the shape of a giant toilet (Bowl Plaza) to a mini Mount Rushmore replica a local artist built in her backyard to the Garden of Eden’s psychedelic-populist concrete sculptures, which put Lucas on the folk art map more than a century ago.

On Main Street, stands Nelson’s other Kansas landmark: a very meta shrine to oversized kitsch called the World’s Largest Collection of the World’s Smallest Versions of the World’s Largest Things.

Inside, a wall-sized U.S. map marks each world’s largest thing’s location with a red dot. Kansas has a lot of red.

“The Northeast doesn’t have that same sort of need to prove themselves in a big manner,” Nelson said. “But there’s this line from Texas up through Minnesota that is just littered with world’s largest things.”

Nelson said these colossal creations particularly resonate with people in Kansas and other parts of Middle America because they elevate the ordinary.

In a region perceived as reserved and understated, she said, putting up the World’s Largest Baseball (Muscotah) or Liberty Bell Made of Wheat (Goessel) offers a subtle way to show pride in accomplishing something extraordinary and unexpected in an often-overlooked place.

“It’s almost like a humblebrag,” Nelson said. “It’s a lot of normal people living their lives who suddenly have this spark and say, ‘Hey, you know what would make this really great? Put an ‘-est’ on it.”

David Condos / Kansas News Service: Erika Nelson intentionally decorated her roadside expo with a carnival theme, including the red and white striped big top that covers her art lab.

Nelson’s fascination with “superlatives” — things bestowed with the title of world’s largest, smallest, tallest, etc. — began as a kid.

She learned to navigate her small hometown in central Missouri based on the town’s water tower, which had been painted by a local billiards factory into the world’s largest 8-ball. Then when she visited her grandparents in Minnesota, catching her first glimpse of the world’s largest Paul Bunyon statue let her know her destination grew near.

As a grad student studying art, Nelson began crafting her own diminutive versions of the world’s largest things as keepsakes from her travels — starting with the one that’s less than an hour from her home: Cawker City’s Ball of Twine.

That was more than two decades ago. She has now created close to 250 of these miniature replicas.

Once Nelson had enough fun-sized water towers and Paul Bunyans to start sharing her collection, she packed them up as a traveling roadshow. Sometimes she displayed them at official superlative events, like the giant ketchup bottle festival in Illinois, or at pop-up shows she held out of the bus that doubled as her living quarters.

David Condos / Kansas News Service: Erika Nelson’s collection of smallest versions of the world’s largest things features several from Kansas, including this tiny replica of the giant travel plate she created in Lucas.

Five years ago, her collection found this permanent home in an old storefront in downtown Lucas.

There’s the “edibles” collection that spans from the largest peanut in Georgia to the largest artichoke in California. Then all the water towers towns have transformed into the world’s largest watermelon (Texas) or ear of corn (Minnesota).

But the centerpiece of Nelson’s collection is a four-foot-by-eight-foot map of Kansas with her tiny models displayed inside clear protective bubbles, from the World’s Largest Electric Coal Shovel (Big Brutus in West Mineral) to the World’s Largest Wren (Topeka) to the micro version of her own World’s Largest Souvenir Travel Plate.

David Condos / Kansas News Service: The World’s Largest Souvenir Travel Plate in Lucas features scenes from local history and culture painted onto a 14-foot satellite dish.

Pioneers of kitsch

When it comes to quirky roadside attractions in Kansas, the Ball of Twine and Big Well are just the tip of the oddball iceberg.

Here’s a small sampling:

-Interstate 70 drivers in northwest Kansas can still catch a small glimpse of Oakley’s World’s Largest Prairie Dog behind the privacy screen that was intended to prevent free looks. Both the giant rodent and the screen are still standing, even though Prairie Dog Town — the unregulated zoo/curio tourist trap that built it — closed eight years ago. Known since 1968 for its bizarre billboards, Prairie Dog Town was also famous for its rattlesnake pit and six-legged cow.

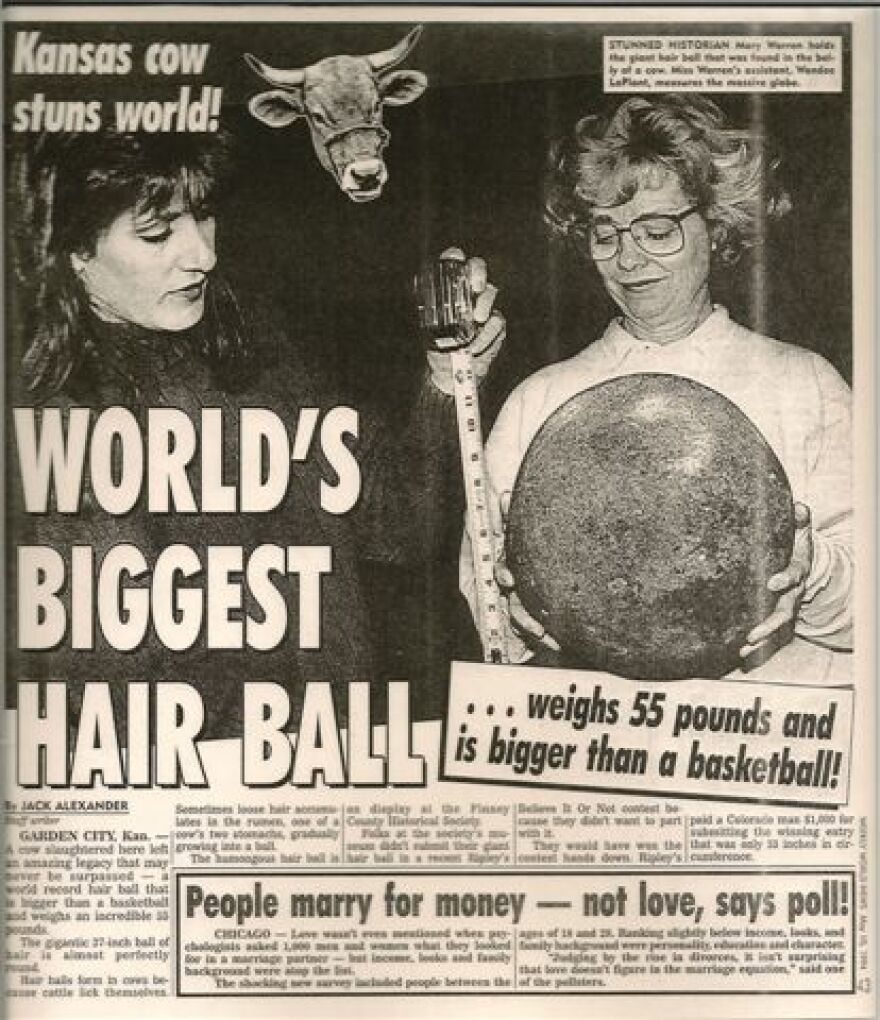

-Garden City claims the World’s Largest Hairball, a smooth sphere of cow hair the size of a beach ball that was discovered in the slaughtering line of a local meatpacking plant in 1993. Visitor reviews say it feels like a velvety basketball. It also has the distinction of gracing the cover of Weekly World News along with Bat Boy and Bigfoot.

Weekly World News / The 1993 discovery of the World’s Largest Hairball in Garden City made the front page of the Weekly World News tabloid.

-And then there’s the Kansas plethora of eccentric festivals. In far western Kansas, Russell Springs — population 28 — holds onto its title as the state’s Cow Chip Capital by hosting a festival each September that includes a contest to see who can throw their poop patty the farthest. Other annual highlights include the Outhouse Festival in Elk Falls, the Barbed Wire Festival in La Crosse and the Cuba Rock-A-Thon, which features three straight days of people rocking in rocking chairs 24/7.

And in Kansas, you don’t even have to be the biggest and best to be celebrated.

Seneca’s claim to fame is being home to the second-largest hand-dug well. Norton built an entire museum dedicated to presidential candidates who finished second (including native sons Bob Dole and Alf Landon). The Big Well museum proudly displays a 1,000-pound pallasite meteorite that used to be the world’s largest but now has a piece of paper with the words “one of the” taped to its sign conceding that it has been demoted by a bigger space rock.

David Condos / Kansas News Service: This meteorite displayed in the Big Well museum used to be the world’s largest, until a larger one was discovered in 2005. It now has the words “one of the” taped to its sign.

And Kansas’ collection of astounding absurdities keeps growing as towns continue to view them as worthwhile investments.

The town of Wilson commissioned the World’s Largest Czech Egg within the past decade. It then took nearly four years of work and $16,000 to get the 20-foot, hand-painted fiberglass oval into place.

Abilene just announced this spring that it’s using $22,000 from the state to build the World’s Largest Belt Buckle, complete with a staircase that will position tourists for a photo of them “wearing” it.

As you can tell, these sites tend to reflect the idiosyncrasies of European settlers, not the Indigenous peoples they replaced. And the few American roadside attractions that do draw attention to non-white cultures, like wigwam village curio shops or giant sombrero-clad men carrying Mexican food, often fall on the side of cultural appropriation and exploitation rather than celebration and inclusion. Nelson’s next project will actually explore how outdated attractions nationwide represent race and what that means for them in today’s context.

David Condos / Kansas News Service: Erika Nelson stands at the entrance to her roadside expo, which she opened five years ago in the small town of Lucas.

But as roadside giants like the Ball of Twine outlast their nay-sayers, Nelson said Kansans’ chutzpah to make something of themselves in the face of long odds and skepticism mirrors the lemonade-from-lemons attitude that has long been key to survival on the Plains.

Like the pioneers who built sod houses and post rock fences in a land without trees. Or the farmers who transformed ground once cast aside as the Great American Desert into the nation’s breadbasket.

“That is very much that pioneering spirit,” Nelson said. “You don’t see what you need? Build it.”

After decades of serving as their towns’ landmarks, the sites themselves are now inextricably woven into their communities’ cultural identities and sense of place. And they almost always hint at a deeper story.

Wilson’s giant egg points to the town’s Czech heritage. Same for Greensburg’s well and the historical importance of underground water in southwest Kansas. Or the tradition of raising cattle in north-central Kansas that led to a giant ball of hay bale twine.

These attractions send a message that there’s more to the story of Kansas than people tend to recognize. And that message isn’t only for tourists. It’s for Kansans too.

“Continually telling your story to outsiders means that you’re reminding yourself of why you built it,” Nelson said. “You’re reminding yourself that this is something special.”

David Condos / Kansas News Service: Linda Clover holds the spool of twine that she uses to help tourists add their own piece to the giant ball.

In Cawker City, Clover said sometimes when she talks with visitors from New York or London who stop to see the ever-growing Ball of Twine, she thinks it might be nice to step into their more cosmopolitan lives for a spell. Just to try out something different.

But then, she remembers that she’s right where she wants to be: Sharing a little bit of her life in rural Kansas with the world — one piece of twine at a time.

“Give me Cawker City,” Clover said. “Give me Kansas.”

David Condos covers western Kansas for High Plains Public Radio and the Kansas News Service. You can follow him on Twitter @davidcondos.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of High Plains Public Radio, Kansas Public Radio, KCUR and KMUW focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.