Hays, KS— Pull off Kansas 156 in Barton County during a wet year, and it might feel like you took a wrong turn into Florida.

This part of central Kansas is home to the largest interior wetlands in the country: Cheyenne Bottoms. It can hold nearly 10 billion gallons of water.

But after months of intense drought, the amount of water in these wetlands today likely couldn’t fill a Dixie cup.

“We are 100% dry. There’s no water on the property,” Cheyenne Bottoms’ wildlife area manager Jason Wagner said. “This year is kind of the perfect storm.”

One of the driest summers on record and months of relentless heat have transformed this oasis on the plains into an empty basin. An endless vista of dry, cracking dirt stretches out where open water once rippled toward the horizon. It’s been that way since June.

That’s especially bad news for the hundreds of thousands of birds that depend on the wetlands as a vital stopover point during their annual migration. Wagner estimates that 750,000 migrating birds stop at Cheyenne Bottoms during an average fall. In the past couple of years, that total has been over 1 million.

This year, it’s basically zero.

“Our bird numbers are nothing,” Wagner said. “Most of them aren’t even stopping because there’s nothing for them to stop for.”

That means the birds — some of which travel thousands of miles along the Central Flyway from as far north as the Arctic Circle down to South America — have to keep flying farther in search of a place to rest.

- This city in Kansas really conserves its water, but that still might not be enough to survive

- Here are 7 ways this dry, hot year stacks up against the worst droughts in Kansas history

- Western Kansas wheat crops are failing just when the world needs them most

- How the drought killing Kansas corn crops could make you pay more for gas and beef

- How Kansas could lose billions in land values as its underground water runs dry

- As fertilizer pollutes tap water in small towns, rural Kansans pay the price

- Kansas wildfire responders brace as a dangerously dry, windy season drags on

- How an increasingly brutal Kansas climate threatens cattle’s health and ranchers’ livelihoods

- A hotter, drier climate and dwindling water has more Kansas farmers taking a chance on cotton

The wetlands normally provide a rare concentration of hard-to-find habitats that offer shallow water, protection from predators and a buffet of aquatic plants, bugs and fish. In a year with such widespread drought, finding another spot that gives the birds what they need to complete their journey won’t be easy.

To the north, the Platte River — another vital stopover point for birds on the Central Flyway — has completely dried up in parts of central and western Nebraska. To the south, drought covers every inch of Oklahoma. It’s a similar story for birds traveling along the Pacific Flyway as drought dries up wetlands and wildlife refuges across California.

Traveling thousands of miles during migration is already physically straining for birds in a good year. So when one of the prime refueling spots suddenly gets pulled out from under them, it could be a matter of life and death.

Alice Boyle, a migratory bird ecologist with Kansas State University, compares it to an ultramarathon runner who’s approaching a rest station along their route where they expect to be handed a cup of water or a banana. But when the runner arrives, there’s nobody there.

“They’re going to try to keep running and go to the next one,” Boyle said. “But not all of them are going to make it to that next one.”

Drylands

The impact of the dry wetlands will be far-reaching not just because of the sheer number of birds that historically rely on this stopover point, but also because of the variety of bird species that will be turned away.

For many of those birds, the solution to a year like this isn’t as simple as merely flying to the next reservoir that has water. Birds have been drawn to central Kansas wetlands for millennia not only for hydration and rest, but also for the food — such as flooded vegetation and blood worms — that places like Cheyenne Bottoms usually have in abundance. Reservoirs often don’t have those on the menu.

Wetlands also protect the birds from being eaten by predators, such as coyotes. The habitat offers them a large space where they can find safety in numbers and cover from vegetation.

“Few areas on the continent have this huge influence on a very large number of species of birds and numbers of birds,” Boyle said. “Quivira and Cheyenne Bottoms collectively are one of those places.”

Cheyenne Bottoms and the nearby salt marshes of Quivira National Wildlife Refuge are two of just a few places in the central U.S. designated as Wetlands of International Importance by the Ramsar Convention because of the critical role they play in aiding birds that migrate along the Central Flyway.

But hardly any of Quivira’s wetland habitat has survived this year’s drought either.

“Things are dry,” Quivira manager Mike Oldham said. “We have at least a small amount of water, but it’s really not enough for migration.”

Right now, Oldham said, less than 30 of Quivira’s acres have any water — that’s around 0.5% of the refuge’s 5,500 acres that would be covered in water during a good year.

Normally, the corridor of central Kansas wetlands would have hundreds of thousands of birds migrate through — everything from snow geese and pelicans to blue-winged teal and wigeon ducks to shorebirds like sandpipers and plovers. It also provides refuge for critically endangered whooping cranes, a species whose total worldwide population numbers in the hundreds.

In past years, upward of 30,000 sandhill cranes would fill Quivira’s skies on a given morning during fall migration. This year, Oldham said, only a few dozen cranes have landed there. And the ones that stop aren’t lingering for long.

“Their choice is: Do I land for the night, rest up on the dry wetland bed and try to stay away from the coyotes?” Oldham said. “Or do I just venture farther south and try to actually hit water?”

Waiting on water

What makes this year’s drought especially bad for birds migrating across Kansas?

Central Kansas has always experienced cycles of drought. Cheyenne Bottoms has been known to dry up periodically, most recently in 2013. But that year, late summer rains refilled it before the fall migration season. To see the wetlands this dry this late into the year, Wagner at Cheyenne Bottoms said, is very rare.

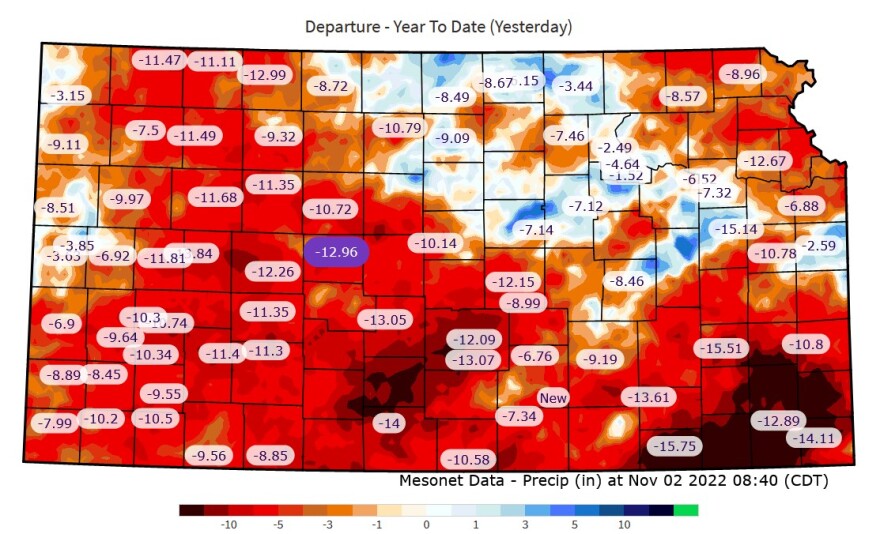

It’s been one of the driest years on record for this part of Kansas. The counties where creeks feed into these wetlands — Rush, Ness and Stafford — are all more than one foot below their historical precipitation averages for the year to date. That means they’d need a foot of rain just to get back to normal.

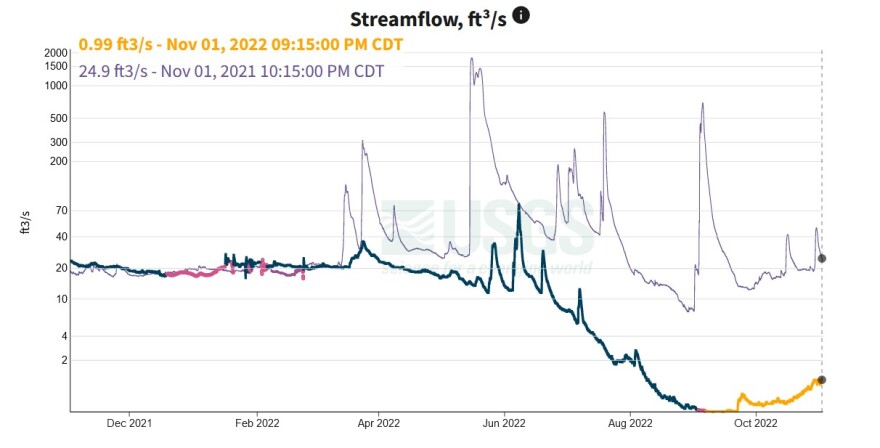

Take the Walnut Creek basin in Rush and Ness counties, for instance. Like nearly all creeks in this part of Kansas, this one has just about dried up. Monitors from the U.S. Geological Survey report that Walnut Creek’s streamflow is less than one cubic foot of water per second, compared with more than 20 cubic feet of water per second at this time last year.

Human intervention hasn’t helped either. Over the past century or so, Boyle said, humans have depleted the underground water supplies that historically boosted the region’s rivers and springs — natural aquatic areas that birds could turn to when the wetlands ran dry. Roughly a third of the water under Kansas has disappeared since European settlement, largely thanks to pumping the Ogallala aquifer for irrigated farming.

Central Kansas also doesn’t have as much wetlands habitat as it used to. Nearby wetlands in McPherson County once rivaled Cheyenne Bottoms, but most of that area was drained more than a century ago and converted to agricultural land. That makes the remaining wetlands that much more critical.

“When we lose one of these important places,” Boyle said, “the animals don’t have the alternative locations to turn to because we’re there.”

The situation is especially precarious because many of these birds have already seen steep declines in population numbers over the past few decades.

It’s estimated the number of birds in North America has dropped by nearly 3 billion — roughly 25% of the continent’s total population — since 1970. Many types of shorebirds have seen even worse population drops, losing more than 70% of their numbers since 1980.

Several birds that typically depend on Kansas wetlands — from the semipalmated sandpiper to the lesser yellowlegs — recently landed on the North American Bird Conservation Initiative’s list of species at risk of losing half of their population numbers in the next 50 years.

For shorebirds, losing the Kansas wetlands as a stopover point could be particularly painful. Many of them only stand a few inches tall, so they can’t feed in the rocky, steep shores of a reservoir in the same way they do in the shallow pools, wet mud and aquatic vegetation of wetlands.

To put it plainly, Boyle said, having a fall migration without the Kansas wetlands means more birds will die. Even the ones that complete the journey to their winter destinations are likely to arrive weaker and in worse health.

Especially for shorebirds migrating long distances, Boyle said, it’s overly optimistic to expect that they’ll just find somewhere else to go this fall. But long-term, the birds’ mobility and flexibility give us reason to hope that their populations can recover if humans do enough to protect their habitat.

“They’ve shown us time and time again, that if you give them half a chance,” Boyle said, “they’ll respond positively.”

As with everything else related to the drought, the big unknown is how much longer it will last. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association predicts a rare triple dip La Niña weather pattern for this winter, which means below-average precipitation in western and central Kansas is likely to continue for at least a few more months.

And for this fall’s migration, it’s unlikely that wetlands conditions will get much better. At this point, Wagner at Cheyenne Bottoms said, it would take several inches of rain just to saturate the dry ground before the wetlands can begin filling with water again.

But there’s at least one silver lining. Wagner spent the morning in a tractor digging up invasive cattail plants in areas that would normally be inaccessible because they’re covered with water. So when the wetland habitat fills up again, he said, it’ll be better than ever.

It’s just waiting on the water.

“One of these days, it’s gonna start raining,” Wagner said. “And we’ll fill back up.”

David Condos covers western Kansas for High Plains Public Radio and the Kansas News Service. You can follow him on Twitter @davidcondos.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of High Plains Public Radio, Kansas Public Radio, KCUR and KMUW focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.